We all know that famous school level physics experiment which shows a feather and a bowling ball falling at the same rate and therefore hitting the ground at the same rate in a vacuum, so of course, all objects fall at the same speed towards the earth regardless of their mass. Right? Wrong. The bowling ball really does hit the ground sooner than the feather, it's just that the difference is incredibly tiny and cannot be measured by normal means.

Heavier objects do indeed fall faster than lighter ones, it's just that seeing the difference in a typical physics experiment simply isn't possible due to that incredibly tiny difference. The reason for this is due to ratios: the earth is so incredibly huge and heavy, while the two objects are incredibly light (even if one weighs many tons* it's still incredibly tiny) and therefore have negligible gravitational fields which can be ignored in everyday calculations. However, if one actually takes into account those tiny gravitational fields, they'll find that the heavy object does indeed fall faster as the attraction between it and the earth is stronger.

Why the hell this isn't taught in schools beats me. I wonder how many other false scenarios like this are being taught as fact. It should simply be taught that the difference is negligible and explain that it's due to the ratios I described above.

In fact, the feather and bowling ball will also move towards each other ever so slightly due to their mutual attraction. Also, that tiny, slow, movement towards each other nicely illustrates what I'm saying. If not, then they'd fall towards each other quickly regardless of mass and distance. What acceleration would it be anyway? You can see how that just doesn't work. It has to be proportional.

It would be nice to know how that difference could be measured in a real world experiment if money were no object.

If I figure out any more, I'll post about them in the forum.

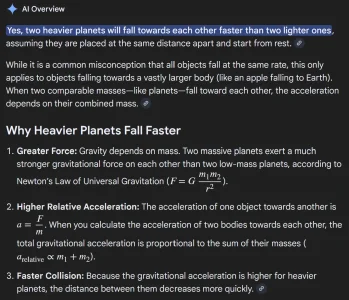

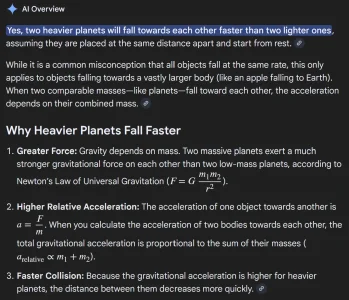

I realised this quite some time ago and it's nice to see it confirmed with a Google search. The question I asked was "Will two heavier planets fall towards each other faster than two lighter ones?" I used the example of planets so that the weights of the two bodies is non-negligible as are the gravitational fields surrounding them. However, this holds true no matter the difference in weights between the objects, even when the ratio is enormous like in the school physics experiment.

Here's Google's AI response:

*It will however make a helluva crash when it hits the ground that would upset the neighbours, especially late at night.

Heavier objects do indeed fall faster than lighter ones, it's just that seeing the difference in a typical physics experiment simply isn't possible due to that incredibly tiny difference. The reason for this is due to ratios: the earth is so incredibly huge and heavy, while the two objects are incredibly light (even if one weighs many tons* it's still incredibly tiny) and therefore have negligible gravitational fields which can be ignored in everyday calculations. However, if one actually takes into account those tiny gravitational fields, they'll find that the heavy object does indeed fall faster as the attraction between it and the earth is stronger.

Why the hell this isn't taught in schools beats me. I wonder how many other false scenarios like this are being taught as fact. It should simply be taught that the difference is negligible and explain that it's due to the ratios I described above.

In fact, the feather and bowling ball will also move towards each other ever so slightly due to their mutual attraction. Also, that tiny, slow, movement towards each other nicely illustrates what I'm saying. If not, then they'd fall towards each other quickly regardless of mass and distance. What acceleration would it be anyway? You can see how that just doesn't work. It has to be proportional.

It would be nice to know how that difference could be measured in a real world experiment if money were no object.

If I figure out any more, I'll post about them in the forum.

I realised this quite some time ago and it's nice to see it confirmed with a Google search. The question I asked was "Will two heavier planets fall towards each other faster than two lighter ones?" I used the example of planets so that the weights of the two bodies is non-negligible as are the gravitational fields surrounding them. However, this holds true no matter the difference in weights between the objects, even when the ratio is enormous like in the school physics experiment.

Here's Google's AI response:

*It will however make a helluva crash when it hits the ground that would upset the neighbours, especially late at night.